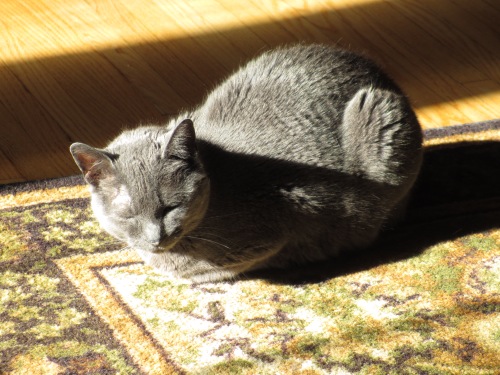

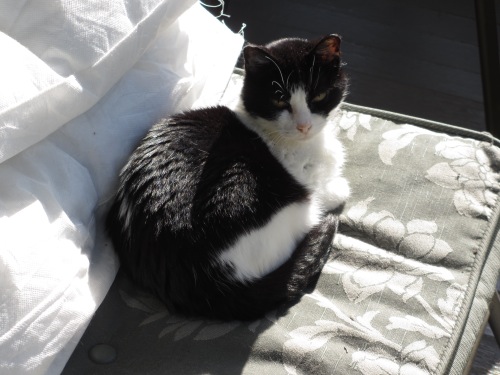

No captions today. Just kitties soaking up sun for the one who is gone.

Farewell Princess

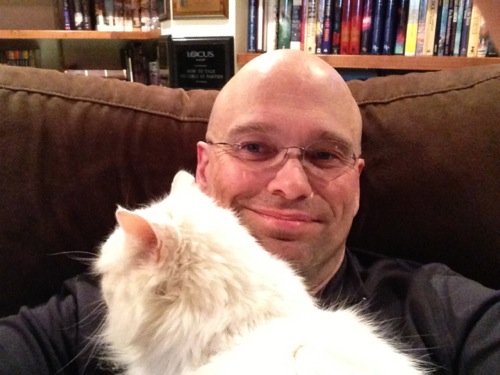

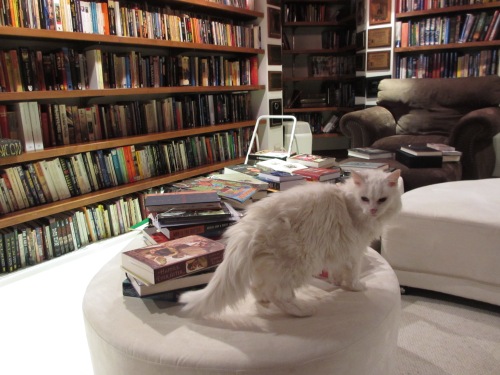

Last night a grand dame of the cat world left us. Princess was the cat of my friend Neil Gaiman. She was a once-wild, wonderful, fierce, old lady with a mean streak a mile wide and fur like white silk. She sent more than one person to the hospital, and spilled my blood on at least one memorable occasion. She was beautiful and tough and more than half a creature of faery. She was also my friend—I visited her nearly daily while borrowing Neil’s running paths—and I loved her dearly. I will miss her, as I know Neil will, along with a whole lot of other people. She touched many lives in her twenty-two-plus years. Because I haven’t the heart for words right now, here are some of my favorite pictures of her (a few have captions because they insisted on it, but most don’t):

This is the very first picture I ever took of her in January of 2011

She loved to drink out of the tap, and insisted that the humans oblige her

She wasn’t often cuddly, but was very fierce about it when she was

This is my favorite shot of her

Because some pictures must be shared

She started drinking out of my glass when she was too tired to go down to the sink

Simply beautiful

She was so fierce

Pretty sure she was trying to figure out how she’d reach the gas pedal

With her long time housemate Coconut

Sleeping in the library

Claiming me for her own

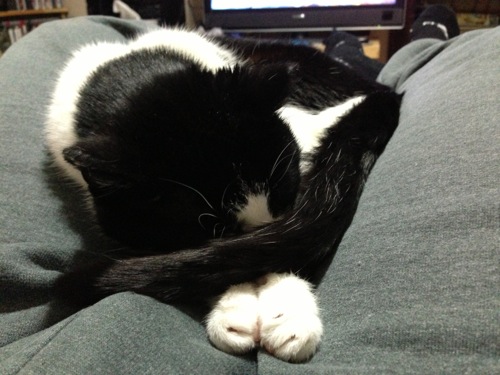

And this is the last picture I took of her—napping on my lap shortly before leaving us

Goodbye Princess, you had a hell of run

Owning Your Work (pt 2 of 2)

Part 1 can be found here.

If you’re fortunate enough to have a good critique group or first readers, you’re going to get a lot of advice on your work, some of it spot-on, some of it close to the mark, and some of it that you violently disagree with. (If you’re not that fortunate, I’d strongly recommend doing something about it as you’ll learn a lot both by getting and giving critique).

The spot-on stuff is easy. You just do it. The close is also pretty easy, as it can be adapted to fit. It’s the violently disagree with that’s hard, because as much as you might like to, you shouldn’t just dismiss it.

Readers offer suggestions because they either 1) disagree with the choice you’ve made, 2) they’ve missed something you expected them to get, or 3) they’ve gone somewhere you didn’t expect. In all of those cases, it’s important for you as a writer to understand why that happened and whether it’s because you didn’t put something down on the paper that was in your head, because you’ve left something sketchy where you should have filled in the details to keep your reader on the path, because you didn’t think of it, or simply because your reader has missed something obvious—it does happen.

The process I go through when I’ve been handed a suggestion that seems to me to come out of left field is thus: 1) put it aside for a moment to see if my backbrain can field the ball and figure out what went wrong. 2) Wait to see if anyone else had the same problem/suggestion, or one that came in the same place. 3) ask questions of the critquer.

That last should be handled delicately. The person making the suggestions is giving of their time and perspective, and you owe them the courtesy of being both polite and respectful no matter how wrong-headed you might think this particular comment is. You’re not trying to defend whatever they’ve disagreed with, you’re trying to find the root of the disagreement.

I try to ask questions like, okay you’ve said X, can you expand on that a bit? Or, if I’ve got an inkling what’s wrong, here’s what I was trying to do there, did that come through? Or, sometimes, what if I told you x about what’s coming up, would that change things?

This is one of the places where the Wyrdsmiths really excel—often, while I’m still trying to figure out what lost someone, another person in the group who has better perspective, figures it out and gives me the piece I need to make sense of the critique, or better still, proposes a solution that fits into the spot-on frame, thereby saving me a ton of work.

Of course, sometimes it comes down to artistic or philosophical differences about where a story should go, and there you have to be willing to say X is going to make some percentage of my readers unhappy and accept the consequences, whatever those might be. It’s not much fun, but it’s what owning your work means.

Update Elizabeth Bear has a link to a post on editorial letters at Blue Rose Girls that’s relevant to the topic at hand.

(Originally published on the Wyrdsmiths blog July 26 2007, and original comments may be found there. Reposted and reedited as part of the reblogging project)

Owning Your Work (pt 1 of 2)

Getting comments and critique on your work is one of the most valuable ways to improve it. It’s also something that you will have to deal with if you’re planning on working with agents and editors. Finding the right balance between doing what’s asked of you and putting your foot down is tough, especially when it could mean killing a deal (always a matter of last resort). There are two main questions you have to ask yourself when you look at a suggestion.

1, does it make the story better? If the answer to this is yes, you move on to question two. If it’s no, you have to take a moment and think about why the suggestion was made (okay, so you should do that if it’s a yes too, because you’ve just been offered a chance to learn something). I was going to talk about this in brief below, but I’ve discovered that it wants to be its own post on rewrites, so more on that later.

2, and potentially much harder to answer, does it advance the purpose of the story? This is the place where things go foggy and vary wildly depending on what sort of writer you are. If you’ve got the whole story in your head or in an outline and someone makes a good suggestion that doesn’t follow along, you’re posed with an immediate dilemma, go with the shiny new thing or stick to your outline. I’ve done both depending on the situation.

My very first short story sale involved taking the second half of a 6,000 word short and throwing it away to write a new ending. I’ve also looked at a beautiful idea and quietly (and somewhat sadly) put it aside. One of the few times I’ve really gotten hammered by a member of one of my writers groups (and rightfully so) was when I let myself slip at the time it was suggested and say that I wasn’t going to do something. I had good intentions, but it was a breach of etiquette and absolutely the wrong way to handle the choice.

In general, if you’re not going to take a suggestion, there’s no reason whatsoever to tell the person who made it, because it will only make them feel as though they’ve wasted effort. There are two exceptions to this. A, editorial/agent suggestions, in which case you discuss the problem the suggestion addresses and try to work out a comprise (more on this in the rewrite post). B, book length works where this person will be critiquing the story on an ongoing basis and where not taking the suggestion will have a significant impact on the reading of the story.

That latter was the case in the scene wherein I got hammered. I handled it the wrong way. What I should have done was shut my mouth and given myself a couple of days to think about it. Then, if I decided it still mattered (it would have in this case) I should have waited for the next meeting and spoken with the critiquer on an individual basis about why the (genuinely excellent suggestion) was incompatible with the novel I was writing.

What they wanted me to do would have made a good story, but it was a story that I had no interest in telling. The only way to stay sane in this business is to write what you love and love what you write. You are the one who is writing it and you are the one who’s name goes on the byline–it has to be something you believe in. You have to own the story.

Part 2 can be found here.

(Originally published on the Wyrdsmiths blog July 23 2007, and original comments may be found there. Reposted and reedited as part of the reblogging project)

Press Releases, A Primer

Yesterday a writing friend sent me a request for help in formulating a press release for a reading for her hometown paper. As I was writing the response I realized the topic might make a good post here. Hopefully Lyda will chime in on the topic to correct or expand on my points since she has more experience with these than I do.

First, a general note on writing press releases.

The main thing to remember is the goals of the press release in descending order:

1. Getting your name and its association with publishing in front of the maximum number of eyeballs.

2. Getting the name of the current publication in front of same along with purchasing information.

3. Promoting the specific event if there is one associated with the press release.

4. Including details that will help the people attached to the eyeballs remember the first three goals in the same order.

5. Everything else.

Now, on to the specifics of the reading release.

Do it in standard journalism reverse pyramid style. Start with the important stuff in the first paragraph, who, what, where, when, why. Something like:

Para 1, Hometown writer, your name here will be signing copies of the title[s] at bookstore x at date and time. If it’s a collection–the anthologies include name’s story title as well as stories by big name authors here. Publisher and purchasing information here with the more prestigious and easily available publications first. Make sure to note that the books will be available at the signing. Updated 2013: Per Lyda’s comments on the original post, it’s always better if you have an event of some kind attached to the press release as that makes it more newsworthy for most journalists.

Para 2, Any other professional awards or credits if you’ve got them. Otherwise go to paragraph 3.

Para 3, this paragraph should be optimized for the specific paper, in the case of the release I mentioned above it’s a hometown paper: Biographical information about your links to the area and how you got your start in writing there–this can be reading stuff, or writing stories for school or whatever. The key is to make the links between this town and your writing. If you’ve got some tie to the bookstore, mention it here. That will remind the readers of the where and make the store remember your name fondly.

Next paragraph on what you write and why.

Further paragraphs expanding on the above.

The key with these is to get the information that the reader needs to go to the event up front and to follow up with why its important in this particular venue and after that a half dozen or so paragraphs of filler and biographical info. When a paper takes a press release that’s the order they want to see things in. Also, finish each paragraph such that the article could end right there. Smaller newspapers are likely to run the whole thing, but big ones will only run as many column inches as they have space for and will stop when they run out whether the press release has ended or not.

(Originally published on the Wyrdsmiths blog July 17 2007, and original comments may be found there. Reposted and reedited as part of the reblogging project)

Friday Cat Blogging

Research and Me, or: The Compost Heap Model

Someone asked me about my research process for the WebMage books. I wrote the following up, and thought it might be of more general interest, as it explains my general model for research.

Most of the research I was doing with the WebMage books was by way of refreshing long standing reading in mythology, specific geographic information for local color, or computer tech stuff. I didn’t have to do a lot of new reading for the series because it’s all stuff (with exception of some of the local color and new tech) that was mostly in my head from years of reading widely in mythology and growing up in a household with both software and hardware computer folks.

In general, I don’t do a lot of research specific to the book I’m working on. I mostly try to read widely in a lot of fields on whatever interests me at the moment and then toss it all into the back of my head where it composts away in the dark for later application to fiction, or inspiration of same.

I wish I could be more specific, but that’s not really how I approach research, except for detail work that comes up as I need it. So, for a theater book, I might realize I need to look at a rehearsal schedule and email someone at a theater to see if I can get a copy. Or, I might realize I need to know what pistol the British military was using in 1939, and go look it up. Otherwise, everything gets fed into the woodchipper and then mounded up for later use.

That’s actually my primary story generation system as well, as things are always crawling out of the compost heap/mulch pile and making a break for it.

Updated to add: Librarians. When I do need those specific bits of information, I often email one my many librarian friends and tap their mad skillz to find the right bits with a minimum of fuss and hassle.

Friday Cat Blogging

I am very unsure about my toes.

I am very unsure about this ledge.

I am very unsure about becoming a bridge.

I am very unsure about the width of this radiator bench.

I am very unsure about the other cat.

I am very unsure about me too.

I am very unsure about the cameraman.

I am very unsure about last night’s whiskey.

I am very unsure if this radiator will keep me safe.

Be sure that it won’t.

The Implicit Contract Between Writer and Reader

Fellow Wyrdsmith Sean M Murphy mentioned this idea in the comments on my original what the author owes the reader post at Wyrdsmiths and it came up a lot at CONvergence 2007, so I thought I’d discuss it. When an experienced reader picks up a science fiction or fantasy story they do so with a number of implicit expectations which form a contract of sorts between the reader and the writer (this is also true for other genres, but the expectations have some variations, so I’m going to focus here on F&SF).

They expect that the story will be about something. They expect that there will be clues and foreshadowing that will point toward the ending. They expect that the author won’t introduce things into the denouement that were not introduced or implied somewhere earlier in the story. They expect things to conform to the general rules and tropes of the genre or for deviations to be explained at some point.

For example, readers expect science fiction to follow the general rules of science. The technology should be of a generally consistent level. Deviations from that norm should be explained either at the time of the introduction of the deviation, or at least noted as being a deviation, with the expectation that the reason will be explained later. If the author wants to write an SF story with magical elements, then the magic had better be shown to exist very very early in the story and there will have to be a scientific explanation (even if it’s just handwaving) somewhere in the story. Likewise, if you’re writing fantasy with elements of sf you want to let the reader know about it early on or at least hint at it.

Another important aspect of the implicit contract has to do with a term I’ve borrowed from science education, the problem statement. Somewhere early in the story, ideally in the first couple of pages, the author has to define the problem that is going to be solved or addressed over the course of the story. The problem can be, the One Ring is a powerful magical device and we will have to learn what it is and what to do with it. It can be Miles Vorkosigan has washed out of military school, what is he going to do with the rest of his life? It can be Corwin of Amber realizing he doesn’t know who or what he is. The answer doesn’t have be resolved as the character expects or wants it to be, in fact in general it shouldn’t be as they expect, though it should be logical and follow naturally from the flow fo the story. But the reader needs to have some idea what to watch and watch for, or they will become increasingly unhappy over the course of the story, and downright irate if the rug is suddenly jerked out from under them somewhere along the line.

Now, it’s possible to do every one of the things I’ve said you shouldn’t, but it has to be done consciously and extremely well or the book is likely to end up traveling in a ballistic arc and lose you a reader, certainly for that story and possibly forever.

(Originally published on the Wyrdsmiths blog July 12 2007, and original comments may be found there. Reposted and reedited as part of the reblogging project)

What Does the Writer owe the Reader?

Fellow Wyrdsmith Eleanor Arnason was on a panel about what the writer owes the reader at WisCon, and she talked about it here . It’s an important question and I really wanted to come back to it. Eleanor’s post included the following:

“Ellen Kushner said writers owe readers the truth, which I guess is true.

I would say the writer owes readers — and herself — the best job she can do.

I tend to believe that the writer owes readers a work that will make their lives better, something they can use in dealing with life.”

I agree with all these points, especially the second one, and yet…I want to say something more.

I guess for me it’s contextual. What story am I trying to tell? Who is the character I’m currently writing? When is the story set? And where? Those are all the sorts of things that will determine what I owe the reader in a given piece. Most importantly of all, what am I trying to achieve with this story?

Sometimes, as in the case of the hard science fiction shorts I wrote for middle school students, it’s conveying good, real, science in a way that lets student see the gears move. Sometimes, I owe the reader a true representation of my core beliefs. Sometimes, if the character disagrees with me, I owe my reader the best arguments I can make against those same beliefs. Sometimes I just owe the reader a damn good ride, or some laughs.

It’s good to write truth. It’s good to give a reader something they can use to make their lives better. It’s good to make a reader laugh or cry or think deeply. But you don’t have to do it all at once. No one story should have to carry everything the writer hopes to accomplish with their fiction.

Picture a story as a boat. Yes, there are great ships that can ferry a life’s work across an ocean—stories that can do everything. But there are also submarines and canoes and even surfboards. Stories that touch you beneath the waterline of the subconscious, or that glide silently across the lake of the mind with a single smart thing loaded amidships, or that just give you a hella ride through the surf. Every single one of them has its proper place and purpose and that’s important to remember.

The key isn’t to do everything every time, it’s to do what you want to do this time to the best of your ability, and it’s okay if all you’re shooting for in a given story is one pure silly smile. Don’t let yourself get trapped into thinking beyond the needs of the story.

(Originally published on the Wyrdsmiths blog July 10 2007 and original comments may be found there. Reposted and reedited as part of the reblogging project)